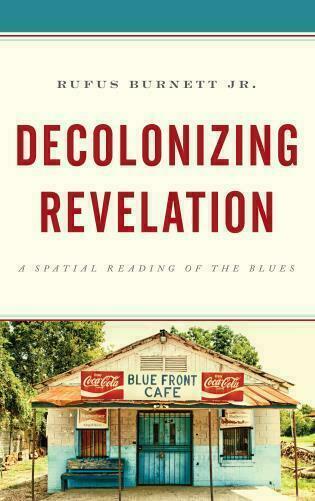

Rufus Burnett Jr., Ph.D., is an assistant professor of systematic theology at Fordham University in Bronx, New York. His research focuses on the sonic, spatial, and embodied realities of the Christian imagination. Burnett's constructive theological approach to systematics looks to expose the theological insight of people groups that respond to domination through the creative use of cultural production. His latest text, Decolonizing Revelation: A Spatial Reading of the Blues, engages the cultural production of the blues as an option for delinking the Christian imagination of revelation, from oppressive foreclosures within nationalism, U.S. Christianities, race, class, sexuality, and ethnocentrism. Burnett previously taught within the Africana Department and Balfour Scholars Program at the University of Notre Dame.

In advance of his visit to Notre Dame and lunchtime lecture on November 15th, 2023, the EITW editors asked Burnett to share his thoughts on the importance of decolonizing scholarship and some of the ways in which scholars can decolonize their thinking, communication, and teaching.

Europe in the World: Why do you think it is important to decolonize scholarship?

Rufus Burnett: So much of the colonial world is about the dynamics of an incongruous exchange amid and between the complex epistemologies of the Americas, the Caribbean, Australia, Africa, and their encounter with Europe. The profound importance of decolonial scholarship rests in the degree to which it illuminates the incongruities of epistemic exchange which frames the struggles against the violence of enslavement, colonialism, and their enduring legacies and afterlives. Decolonial scholarship is important because it holds institutions, academic disciplines, faith organizations, and ordinary people accountable to the challenges wrought out of the struggle of ordinary people fighting for spaces that allow them to live out their visions of a good life in substantive and meaningful ways. Decolonial scholarship is about a historical honesty that can fuel a political option for those in struggle who are deemed less than or insufficiently human and thus do not make a demand on practitioners of the liberal democratic project and its notion of freedom, justice, and human rights. One important thing decolonial scholarship must do is to expose “civilization” as a sociality that could and should be otherwise.

EITW: What methodologies do you employ to do this work? (e.g. archives or sources used, interdisciplinary approaches, etc.)

RB: At the moment I am using methodologies from Latin American decolonial theorists, critical geography, and black studies (particularly the work of Hortense Spillers, R.A. Judy, and Zakkiyah Iman Jackson). As a constructive theologian I am learning from the way in which these methods theorize, chronicle and interpret the darker side of western modernity with an eye towards rethinking and retelling the stories of struggle and existence in the modern/colonial world. These stories when read from a theological perspective open up ways of rethinking theological ideas.

EITW: When you are addressing different audiences (e.g. students in a classroom, the public, other scholars in your field), what do you have to bear in mind? How do you adapt your approach?

RB: Probably the most important thing I must bear in mind is that most people gain access to decolonial thought in the halls of the academy even if those halls are the less traveled ones. As such, most people think they know the use value of “decolonizing” as if it is a garden variety tool, a hammer, or a wrench. In some instances, most people assume that decolonizing anything is simply aimed at making that thing better in a generic or easily identifiable way. For instance “decolonizing the syllabus” typically means adding non-European thinkers who may or not be epistemologically discordant with Eurocentrism. Most people don’t know the level of depth to which decolonial movements work to abolish or end the ideals on which coloniality is based. I begin with really basic narratives, Enrique Dussel’s, Invention of the Americas is an example. One hypothetical story I tell is about a visitor that enters someone’s home only to forcefully deconstruct the familiarity that one has with their home. The visitor makes the bathroom the bedroom. The kitchen becomes the office, the bedroom becomes the kitchen, and so on. Then I tell the student to imagine that this happens to them and it goes on for not only their lifetime but many lifetimes. Then I simply say, “What would it be like to be consumed by the visitor's vision of life.” Most folks can imagine the violation of a home invasion but they cannot imagine that violation taking hold over centuries unless they are the descendants of that violation and are forged in a living and embodied local history.

EITW: How can we incorporate decolonizing materials into our teaching? Are there any strategies you recommend?

RB: Stories, Stories, and more stories. Cacique Hatuey, Nat Turner, Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Harriet Tubman, or everyday ordinary people/people groups that embody the spirit of decolonial struggle or that carve out a life under the imposition of the coloniality of power. Also, incorporate music and visual art, particularly the art born out of a sustained working out of an alternative to the coloniality of being, power, and gender.

EITW: Can you provide a short list (4-5) of writers or texts that inspired you to pursue this work?

RB: Certainly. In my opinion, the following list of authors and/or texts provides a valuable contribution to pursuing this scope:

- Steven Battin

- Charles Long, Significations

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin White Mask

- Delores Williams, Sisters in the Wilderness

- Marcella Althaus Reid

- Vine Deloria, God is Red