The Celtic Tiger years (from the mid-1990s to the late-2000s) led to rapid cultural changes in Ireland. The economic success of the Celtic Tiger reversed Ireland’s historic outward emigration to inward immigration. Ireland became a lucrative destination for immigrants because the Irish State encouraged immigration to satisfy the growing demands of the labor market that the economic boom had created. From 1995, non-Irish immigrants started coming to Ireland in significant numbers. Between 1995 and 2000, the non-Irish immigrants comprised individuals from the United Kingdom (18%), other EU countries (7%), and non-EU countries including the United States (19%). In the following years, work permits granted to migrants from non-EU countries grew exponentially indicating increasing cultural and ethnic multiplicity in 21st-century Ireland. But soon enough, negotiating with the newfound cultural plurality turned out to be challenging for the country. The 2004 citizenship referendum and the Direct Provision system, according to experts, have indicated Ireland’s reluctance to welcome refugees and asylum seekers. In this piece, I illustrate how immigrant Irish authors of color negotiate with a sense of unbelonging and develop flexible affiliations with their host country.

Whereas depictions of Irish multiculturalism by native Irish authors serve the essential function of delineating the inherent diversity of Ireland, they have also been occasionally criticized for misrepresenting, oversimplifying, or idealizing the experiences of the immigrants.

Recent Irish literature and artworks capture, in various forms, the multiculturalism of post-Celtic Tiger Ireland. Various writers, such as Roddy Doyle, Chris Binchy, Mary O’Donnell, Oona Frawley, and others, have depicted the encounters between Irish natives and Irish immigrants and have illustrated how such encounters lead to potentially hybrid identities. Whereas depictions of Irish multiculturalism by native Irish authors serve the essential function of delineating the inherent diversity of Ireland, they have also been occasionally criticized for misrepresenting, oversimplifying, or idealizing the experiences of the immigrants. For example, Amanda Tucker has criticized Roddy Doyle’s The Deportees (2007), a well-known collection of stories on Irish multiculturalism, for “gloss[ing] over systemic problems by focusing on the individual.” She writes that the Irish characters in these stories “accommodate the non-Irish-born, but only for a limited amount of time, and after providing a warm meal, a listening ear […] they resume their normal lives.” Similarly, Oona Frawley’s 2014 novel Flight also elides many of the difficulties of immigrant experiences. According to Anne Mulhall, the novel ultimately re-centers whiteness.

In contrast, works by Irish migrant writers of color reveal the heterogeneity of migrant experiences and de-center whiteness. Their works carefully reveal the complexity underlying the multifariousness of modern Irish identity. Among contemporary Black immigrant Irish authors of African origin, Melatu Uche Okorie’s works stand out as she records the experiences of Black immigrants in post-Celtic Tiger Ireland and depicts how immigrants encounter various obstacles while trying to create a sense of belonging with the host country.

It should be noted that the categorization “migrant writers,” can lead, as Mulhall points out, to racialization, dehumanization, and ghettoization of authors. Indeed, the categorization can minimize the crucial role such authors play in modern Irish literature and misleadingly suggest that migrant writers are somehow peripheral to the Irish canon. In this piece, the denominator “migrant writer”is being used to emphasize that the author(s) examined here are not ventriloquizing migrant experiences from the position of longstanding Irish natives. Instead, these authors are drawing on their own experiences of immigration to Ireland and they approach modern Irish identity with all its intractability.

Black immigrants of African origin often encounter various obstacles in their process of fostering a sense of belonging with Ireland. The reasons why Black Africans migrate to Ireland range from dysfunctional social facilities, political crises, and economic hardships in the home countries to aspirations for better life and opportunities, enhanced status, and improved professional prospects in the host country. However, they often encounter discrimination in the Irish labor market where they are forcibly employed in jobs for which they are overqualified. They also face issues in the housing market where Irish landlords are sometimes reluctant to rent to black tenants. Moreover, the 2004 constitutional referendum to remove citizenship for children born in Ireland to non-Irish parents created further impediments in the process of integration since it induced the anxiety of deportation for several thousand African immigrants. Additionally, the Direct Provision system restricts everyday interactions between asylum seekers and local communities and hinders cultural exchange between immigrants and natives.

The process of developing cultural hybridity for Black immigrants of African origin in Ireland is thus disrupted by various impediments. Furthermore, Black Irish authors find it challenging to publicly discuss their experiences. Many migrant artists of color struggle to find publishers and choose alternate routes of self-publication―cases in point are Ifedinma Dimbo’s She was Foolish? (2012) and Ebun Joseph Akpoveta’s Trapped: Prison without Walls (2013)―or spoken word and live performances.

Melatu Uche Okorie captures in her short stories the experiences of Black immigrants of African origin in Ireland who navigate these impediments. She draws on her personal experience of coming to Ireland from Nigeria more than a decade ago in her writing. In one of her short stories, “Under the Awning,” she illustrates “the everyday racism that most African people living in Ireland have faced.” In the narrative, a nameless girl shares a story she has written about a teenage Nigerian girl and the character’s anxieties about living in Ireland. The author-character in the story lists many moments of contact between the Nigerian girl and Irish society and describes how they lead to a sense of insecurity and eventually create a state of paranoia on the part of the girl.

“Under the Awning” shows how the 2004 citizenship referendum created a sense of unbelonging among immigrant/“non-national” children. It depicts a moment in a school where “all the children’s pictures were put up on the wall with their countries of origin written above it and how the children with non-national parents had their parents’ countries of origin.” The teenager tries to fit into a society that is sometimes openly hostile towards her: children in the street call her “Blackie,” fellow passengers do not take the seat next to her in a crowded bus, and her classmates loudly express concern about losing their wallets when she is around. Such adverse encounters induce paranoia in her and she mistakes even good-natured communications―a lady talking about the weather―as covertly antagonistic. Okorie’s story exposes moments of conflict between immigrants and natives and denies a fantasy of harmonious unification between the two communities.

Declan Kiberd, in his renowned 2001 essay “Strangers in their Own Country: Multiculturalism in Ireland” drew attention to the fear of hybridity that has historically plagued Irish society. He wrote that to prevent being co-opted by the imperial English culture, the Irish adopted the counter-strategy of assimilating cultural otherness and thereby constructing a mythically ‘pure’ Irishness. The waves of inward immigration in Celtic Tiger and post-Celtic Tiger Ireland threaten the assumed racial and cultural homogeneity of Ireland. Migrant writers like Okorie reveal the particular complexities of developing a hybrid identity experienced by immigrants in Ireland.

Further recommended reading on the subject

- www.asylumarchive.com: This is an online archive of photographs and other materials documenting current and former Direct Provision centers in Ireland. The website also features writings about Direct Provision by survivors and those currently living within it, as well as by activists and academics.

- The Black and Irish Podcast: This series of podcasts discusses first-hand accounts of lived experiences and personal stories from the Black Irish community.

- RTÉ (Ireland’s National Public Service Media), “Correspondences—the anthology giving voice to direct provision,” June 4, 2020, https://www.rte.ie/culture/2019/1210/1098209-correspondences-the-anthology-giving-voice-to-direct-provision/.

- Bryan Fanning, “Immigration and the Celtic Tiger,” in Eamon Maher and Eugene O’Brien (eds.), From Prosperity to Austerity: A Socio-Cultural Critique of the Celtic Tiger and Its Aftermath (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014).

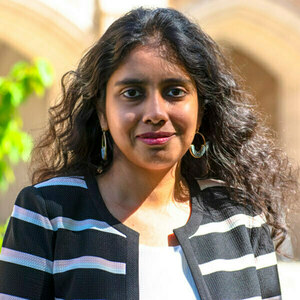

About the author

Shinjini Chattopadhyay is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of English at the University of Notre Dame, pursuing minors in Irish Studies and Gender Studies. She completed her M.A. and M.Phil. in English Literature from Jadavpur University, India. She works on British and Irish modernisms and global Anglophone literatures. Her dissertation investigates the construction of metropolitan cosmopolitanism in modernist and contemporary novels. Her articles have been published or are forthcoming in James Joyce Quarterly, European Joyce Studies, Joyce Studies in Italy, and Modernism/Modernity Print+. Find out more about the author here.

Credits: Image source