The epic genre, as Giambattista Vico notes, tells the story of a nation’s coming to acquire knowledge of itself and its destiny through the vicar of some central hero – an Achilles or an Aeneas. György Lukács (The Theory of the Novel

A Historico-philosophical Essay on the Forms of Great Epic Literature, the MIT Press, 1974) sees the novel continuing this older tradition in a world where destinies and fates are products of personal choice and temperament rather than divine predestination. We see the mythical nation make way for the rational and bureaucratized state, whose operations are too complex for an individual to identify with. The novel’s irony-ridden anti-heroism is a manifestation of the imperviousness of the world.

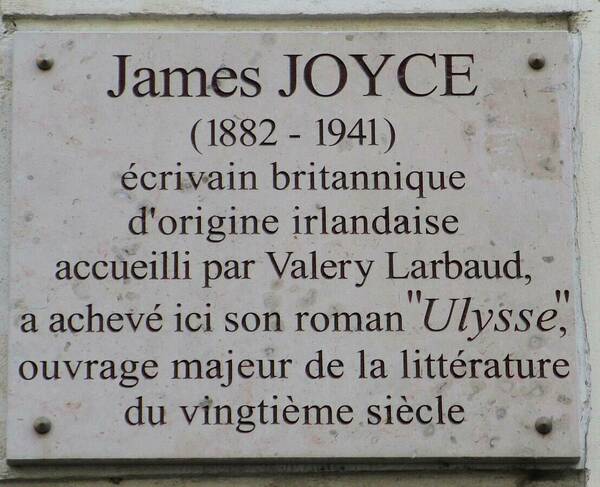

James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) takes a lot from and adds something to Lukacs’ novel. Its two central characters are, like Lukacs’ paradigmatic anti-heroes, alienated from their cultural world — pre-independence Ireland at the turn of the twentieth century. However, Ulysses’ comedy exceeds Lukacs’ romantic alienation. It features the transcendence of a relationship between two figures of their world and offers a glimpse of a potential non-national and non-religious foundation to address human disconnection. In what follows, we will wander with Stephen Dedalus and Leopold “Poldy” Bloom from their estrangement to the estrangement of their estrangement. Joyce urges us to consider the possibility of a self-ascribed narrative of the present to address the loss of a socially prescribed one of the past and the future. Ulysses immortalizes just one day in the lives of these men: June 16, 1904.

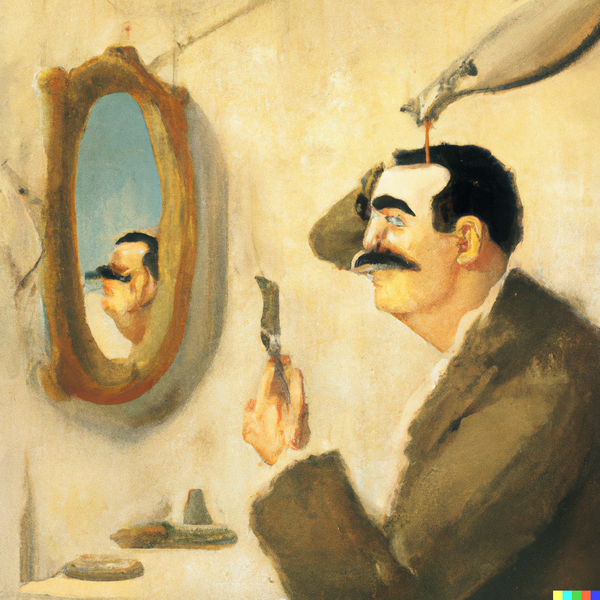

The novel begins with a compound image of its two preoccupations: the nation and the church. On top of a former English naval fort on Ireland’s coast, Malachi “Buck” Mulligan shaves his face while blessing the dawn in Church Latin: “Introibo ad altare Dei” (I will go up to the altar of God), while his unshaved head mocks the devotion of the tonsured monks. In place of the Cross, we see a razorblade, and its use requires a mirror — a vanity for man’s self-regard and self-love. Stephen Dedalus joins Mulligan in this ceremony.

Dedalus is immune to the charm of Mulligan’s travesty, but only because he is close to Mulligan in his capacity for blasphemy. A dispute helps illustrate this. Stephen is angry with Mulligan for suggesting that his mother is “beastly dead.” This hurts him not just because it is a horrid image to put to a woman’s horrid death (she has died of liver cirrhosis, hacking up green bile, which Stephen’s poetic imagination equates to the green jelly of the sea — the “Mother of us all”), but also because Stephen refused to honor her request to kneel and pray for her at her deathbed. Stephen is an atheist whose conscience is pricked by his unbelief.

What is to replace his lost belief and lost nation, his religion and barracks, his home? Later in the long day, when Stephen has finished teaching, an exchange between him and headmaster Deasy answers that question in part.

Deasy remarks that “England [and, by extension, Ireland] is in the hands of the jews.” He subscribes to the view of history, developed/popularised by the philosopher Hegel, as the march of God in the world, believing that history is a series of triumphs by the civilized state over barbarism, even if this triumph is purchased at the price of barbarous violence. In this view the nation becomes the center of spiritual life and permits the chauvinism of Deasy’s statement. The Lukacsian anti-hero is allergic to this; Stephen views history and its anti-semitic, triumphant God as “a nightmare.” His vision of God is “a shout in the street” that awakens; it is a brief burst of joy, emotion, and sensuality.

But this God does not yet command Stephen’s full respect, who shrugs as he introduces Him. Stephen is a heresiarch and an inveterate philosopher who cannot escape the God of the intellect, the God of the philosophers, the nation’s God. For as long as Stephen remains a Jesuit without the belief, his God is the God of Sabellius (“the subtlest heresiarch,” who “held that the Father was Himself His Own Son,” that the trinity was one) — self-conceived and self-born.

Who will save Stephen from this God and from his unbelieving belief?

Leopold Bloom is an ad canvasser for the Freeman, a Dublin daily. He is also Jewish, a cuckold, and a minor miracle worker. In him are united all contrarieties. He is estranged from nearly every possible level of human identity and relation: religious, national, personal. Yet there is no figure so bursting with good spirits and sensuous life.

The sensual Bloom habitually eats “with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls.” At Dlugacz the butcher’s, Bloom, Jewish, opts for a pork kidney wrapped in a piece of newspaper advertising the purchasability of fertile land north of Jaffa in the Holy Land. Uninterested, he eats his kidney with relish. The riddle of Bloom’s Jewishness deepens as we learn about his past. His father, Rudolf Virag, was a Hungarian Jew who converted to Protestantism to marry his mother. Bloom is troubled by this father’s memory: he was a suicide.

Death is also the ground of Bloom’s cuckoldry. Molly sleeps with the “worst man” in Dublin, Blazes Boylan. Bloom forgives her for this; their relationship has suffered greatly due to sadness provoked by the death of their infant son Rudy. His child’s ghost literally haunts Bloom. A “mariolatrous” Jew, who converted to Catholicism to marry Molly, Poldy is both insubstantial and consubstantial. He is a Jew who is not a Jew, a husband, father and son who is no longer a husband, father and son, and an Irishman who is not an Irishman. Somehow in combining all these opposites, he is a sensualist with a heart.

Bloom is the riddle of history solved, even though he does not know himself to be this solution. As he blunders his way through the day, he unwittingly fascinates his fellow Dubliners with a prophetic aura that he himself cannot see.

His is what Walter Benjamin calls a “weak messianic power,” which redeems history by enabling all of its moments to be “citable”, worthy of being retold. At the funeral of Paddy Dignam, Bloom is puzzled by the presence of a thirteenth member of the party – an anonymous man wearing a macintosh. When the members of this funeral party are requested to sign their names in a guestbook, the others ask Bloom for the man’s name:

—And tell us, Hynes said, do you know that fellow in the, fellow was over there in the…

He looked around.

—Macintosh. Yes, I saw him, Mr Bloom said. Where is he now?

—M’Intosh, Hynes said, scribbling, I don’t know who he is.

The presence of “M’Intosh” at Dignam’s funeral is registered in the newspaper.

Such moments show Bloom remaking the world, impregnating it with meaning so that more and more of its facts become “citable” without changing anything at all. The anonymous of history are named, if in an instance of mistaken identity. Vladimir Nabokov suggests that this anonymous man was Joyce, the creator himself. What if he was indeed “the Logos who suffers in us at every moment,” who suffers with us? What if Bloom named the mysterious, anonymous veil that cloaks Being itself? Then God would be a misheard shout in the street.

In Bloom’s mouth, the invocation of God is merely the invocation of the mystery of a personal, suffering God. A God who is therefore alien to the totalizing projects of man, including that of the state. Bloom’s God instructs man to renew the quest for the authentic community that he claims to have founded finally, once and for all, in God’s name, which, in the mouths of the philosophers and the statesmen, stands for the self-enclosure.

The encounter outside of public time between Bloom and Dedalus, whose paths cross several times throughout the day, is a glimpse of their possible redemption. Stephen’s problem is with Irish nationalism and Bloom’s with the fact that despite wandering from his Jewish identity he is not Irish, and neither will a son of his ever be. When Stephen is knocked out in a fight with a British soldier, Bloom the Jew picks Dedalus the Greek up in “orthodox Samaritan fashion.” Bloom brings the younger man to his house with the secret intention of introducing him to Molly, to whom Stephen will give Italian lessons and possibly sleep with, by Bloom’s design. Bloom reasons that if Molly has to sleep with someone other than him, better with Stephen than with the worst man in Dublin. Molly might even agree with this calculation.

National and religious barriers are crossed in their fraternity, even though neither is representative of the race they claim to descend from. As one character’s cap in the novel’s hallucinatory “Nighttown” sequence puts it: “Jewgreek is greekjew.” In a touching final moment, the two urinate together while examining the night sky, for the day is done. If the God who is just a shout in the street has a heaven, certainly it would be one in which the intimacy of shared alfresco urination under the night sky is the common scene, rather than the beastliness of the throng or spurious fraternity of the secret society. Not being as rank a sentimentalist as this piece has perhaps led the reader to believe him to be, Joyce never says whether this intimacy is enough to restore Stephen to the fold while keeping his atheism intact. Really, though, if anybody were up to the task of doing such a thing, it would be Bloom — the materialist with a heart, the father of nations without a nation.

The novel closes with an image of two wanderers, strangers to the world, who are made less strange by an even deeper strangeness and given some inner compass that will point to renewed wandering.

Endnote

1. The author follows Richard Ellmann’s symbolist reading of the book in Ulysses on the Liffey (Oxford University Press, 1986).

Further recommended resources

- Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940)

- Samuel Beckett, “Dante... Bruno. Vico.. Joyce,” in Finnegans Wake: A Symposium - Our Exagmination Round His Incamination of Work in Progress (Paris: Shakespeare & Co., 1929), pp.1-22.

- Anthony Burgess, Joysprick: An Introduction to the Language of James Joyce (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1981)

- Richard Ellman, Ulysses on the Liffey (Oxford University Press, 1986)

- Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Russian Literature (1981)

About the author

Seaver Holter is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Notre Dame. He is interested in Greek and German political thought.