1923 and 2023

When my uncle passed away earlier this month at the proud age of a hundred years, I sat back to imagine what the world was like when he was born in 1923 and compared it to the present.

In 1923, Germany’s Weimar Republic was facing challenges on all fronts. France and Belgium had occupied the industrialized Ruhr Valley to enforce reparation payments in goods instead of inflation-riddled currency. 2023 too has seen its share of inflation. The extent of the current financial challenges pales in contrast to Germany’s hyperinflation which peaked at the staggering devaluation of 4.2 trillion marks per dollar. However, the fact remains that the geopolitical and financial developments of today have many people worried.

In 1923, these struggles, paired with the traumatizing memories of the Great War, left little room to thoroughly solve the cultural conflict of the late nineteenth century between the Prussian government and the Catholic Church. The Kulturkampf had officially been laid to rest in 1887 (when Pope Leo XIII famously stated that it hadn’t but harmed both the Church and the State). But while open confrontations had ceased, distrust between Catholic and secular academia carried on. Is the structural disconnect between scholarly positions due to opposing worldviews another point of comparison between then and 2023?

In 1923, new and far more perilous tensions were rising in Germany as Hitler orchestrated his Beer Hall Putsch. Although unsuccessful in that moment, Hitler’s coup d’état reminds us that the build-up to his eventual rise to power occurred amidst social unrest and political polarization. The latter clearly afflicts us, too, in 2023.

And in 1923, Romano Guardini gave his inaugural lecture at Berlin’s Friedrich-Wilhelm-University. While a less imposing event, the ideas of his lecture seem relevant again today, precisely because of the polarized atmosphere reigning in Church and culture—both in 1923 and 2023.

The context of the lecture

In the cultural stronghold of Berlin, which, for all its dazzling pluralism, was entirely characterized by liberalism and Protestantism, Guardini’s new position was as challenging for him as it was provocative for many of his academic colleagues. Nevertheless, it was the Prussian Minister of Culture, Carl Becker, who had suggested his appointment. A capital city that had recently begun to function according to republican principles, and even more so a cosmopolitan university in the wake of the Kulturkampf, finally had to give Catholics a chance to present their medieval-looking ideology. Thus, a visiting chair had been set up and Guardini was appointed to teach a class on "Catholic Worldview".

As he commenced his work, Guardini recognized a whole generation in the two or three dozen faces that attended his class—embarrassed, calculated, or expectant. Indeed, he spoke to a culture that, for all its eccentricity, was profoundly disoriented and agitated by questions about the meaning of life.

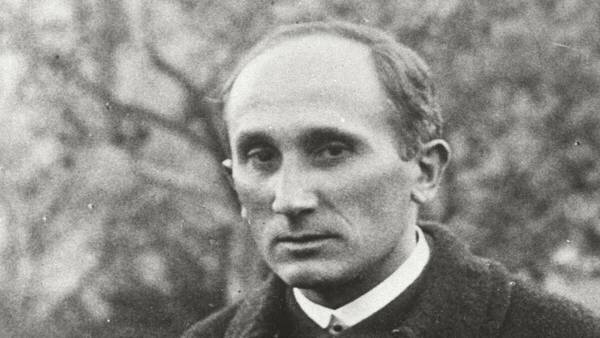

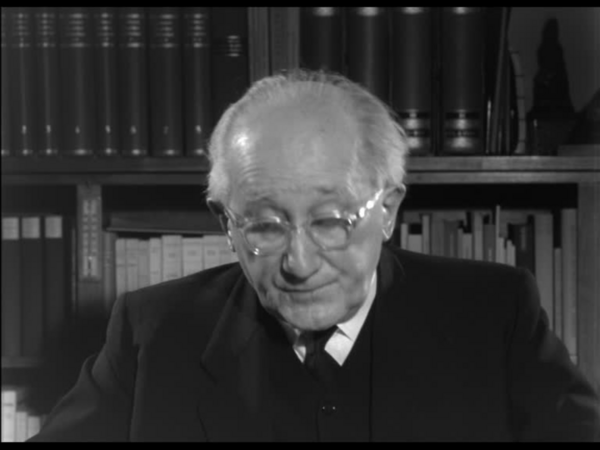

Who was Romano Guardini?

Guardini was himself a part of that generation. When he had been to Berlin for the first time eighteen years earlier, in 1905, he probably could not have imagined his present appearance. The twenty-year-old had lacked any clear direction. Despite his great interest in art, he first studied chemistry and then politics.

His family had immigrated to Germany when Romano was an infant. Overcoming the schism between his Italian home and the German culture was his first task after leaving the nest to begin his studies. He would later describe how, during those difficult and eventful years, there was a "conversion" so strong that it renewed his commitment to the Catholic faith and later even moved him to study theology and join the seminary.

When Guardini was called to Berlin in 1923, he had been a priest for 13 years but had only been habilitated as a professor since the previous year. As a chaplain, he gained experience in youth education and pastoral care (he famously led the Quickborn Youth Movement and was very involved in the liturgical movement). He had even made a name for himself in Catholic circles in 1919, with the publication of his booklet "On the Spirit of the Liturgy."

When the University of Berlin assigned him a chair with the title "Catholic Worldview," he set out to elaborate—in close dialogue with his friend Max Scheler—a systematic reflection about the en-vogue term “worldview.”

What is Catholic worldview?

A worldview is the lens through which a person looks at the world. “World” in this context means the coherent totality of reality as perceived by the beholder. Worldview is the tendency of humans to integrate any input into this wholeness so that everything somehow fits into the "story."

As Guardini notes in his lecture, a worldview is not only a lens to view the world and a story to relate experiences but also a standpoint from which to regard reality. This standpoint aims to be independent of the ever-shifting world. Typically, a worldview will consider this standpoint to be an absolute truth. Freud describes this quite similarly when he writes:

"A worldview is an intellectual construction that solves all the problems of our existence uniformly from a superordinate assumption."

The Catholic worldview would hence be the view of the world from the standpoint of the Catholic faith, with the opinion that it is based on an absolute truth.

Instead of apologetically justifying the claim to truth—with an eye on the skeptics clearing their throats in his Berlin lecture hall—Guardini instead invited his listeners to examine the effect of the Catholic worldview in history. What happens when people take the standpoint of faith and look at the world from there?

Astonishingly, the Catholic worldview does not lead to ideological uniformity. Catholics have interpreted the world in multiple ways. Specifically, Guardini recalls the differences among figures as great as Augustine or Ignatius, Aquinas, or Newman.

"Undoubtedly, they were all Catholic, but equally unquestionably different in the way the world appeared to them. And we immediately feel that it would be a disservice to these personalities and their work to bring them into line. Not only would it be untrue, but irreplaceable things would be destroyed; we would impoverish the rich Catholic world."

So, which of these worldviews is Catholic? All and none. Each of them is unique; but above all partial. To reduce Catholicism to one of them would be a "disservice."

Only one Catholic worldview can be claimed to be the Catholic worldview par excellence: the encounter of Christ with the world. If from here we describe revelation as participation in this gaze of God on the world, an essential insight of the "Catholic" opens up to us. For Christ has not bequeathed this participation in his gaze to an individual; nor has he written it down in codified form; rather, he has entrusted it to a community: the Church.

The individual disciple, standing in history and their own temperament, will only be able to internalize and adopt the gaze of Christ according to a certain type. But what is essential about the gaze of Christ is precisely that it is not worldly, partial, and culturally relative. From the beginning, Christ was careful to entrust his message to a living community of people whom his Spirit continues to animate: twelve apostles, 72 disciples, groups of devout women, four evangelists, a college of bishops, and a people of God. In and from the Church, Christ's gaze on the world can be carried out anew, according to all possible types, in all places, and at all times.

Thus, the Catholic worldview, in Guardini’s sense, does not play the role of yet another voice in the chatter of ideological positions. Rather, it is called to integrate all that is good and true within the different perspectives into a wholesome and holy view of the world.

Suggested further reading:

- Gabriel von Wendt, Catholic Worldview. Glances at Cultural Change, BoD (2023).

- Gabriel von Wendt, “Yes. A Remarkable Response to Cultural Change.” In: QUIEN (7/2018), pp. 119-143.

- R. Guardini, “Vom Wesen katholischer Weltanschauung” (1923). In: Unterscheidung des Christlichen (1994), pp. 21-43 (not yet available in English).

- R. Guardini, The Spirit of the Liturgy, translated by Ada Lane, Cluny Media (2018).

- Heinz R. Kuehn (ed.), The Essential Guardini. An Anthology of the Writings of Romano Guardini, Liturgy Training Publications (1997).

- Todd H. Weir, Secularism and Religion in Nineteenth-Century Germany, Cambridge University Press (2014).

About the author

Gabriel von Wendt (Dr. des.) teaches cultural philosophy at the Pontifical Athenaeum Regina Apostolorum in Rome, Italy. Since his undergraduate studies in philosophy, he has studied the life and work of the Italian-German thinker Romano Guardini. He is interested in the effects of cultural changes on human existence and in the role of Catholic figures in culture throughout history.