Throughout history, Christianity has taken root in the Greco-Roman and European cultures. But in the 20th century, the culmination of a long process of secularization in Europe is calling into question the expression "Christian West." Faced with this reality, what stance should theologians and Christian thinkers take? Christianity firmly believes that there is only one Savior: Jesus Christ, and so religious relativism should be rejected. But what should the believer think of those who are not Christians?

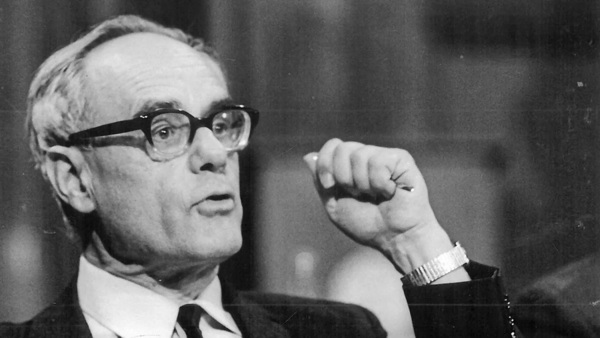

One of the most influential European theologians in the 20th century, the German Jesuit Karl Rahner (1904-1984), sought to answer this question with his theory of the “anonymous Christians.” This idea has caused a stir in Catholic circles. If non-Christians can experience salvation without a visible link to the Church, is missionary work still necessary? These are the concerns we will attempt to clarify in this contribution.

It is impossible to understand the thesis of the anonymous Christians without seeing the broad outlines of Rahner's theological anthropology. Two concepts borrowed from modern philosophy come to the fore: the transcendental and the categorical. Transcendental is the athematic horizon, the implicit condition of possibility of the categorical such as concrete, historical experience. Our will, desire, and knowledge as concrete, thematic, and elaborate experiences are "categorical." But thematic activity is made possible by another pole, a concrete and non-thematic, much harder to describe because it eludes any attempt at classification. This is the transcendental pole.

The horizon of thought of this transcendental pole is infinite. The subject is pure openness to everything, to being in general. The human is defined as this openness to all reality. They live in the finitude of the categorical, but they are always inhabited by this desire for the infinite. The human being finds themself in this imbalance between the finite experienced and the infinite desired. The infinite horizon of transcendental experience leads to an absolute and sacred mystery, the one we call God. At the same time, transcendental experience gives us an implicit and "anonymous" knowledge of God.

The quest for the mystery of God that is given in transcendental experience is a gift of God who wishes to communicate himself. It is as much an ascending experience of humanity, as a favor from God wishing to communicate himself. This initiative of God, who intervenes at the original pole of man's consciousness, is technically termed supernatural existential by Rahner.

For Rahner, then, there are two dimensions of Christianity: on the one hand, anonymous Christianity, which is the implicit, transcendental disposition of every human being in his or her existence to divine Revelation, and on the other, plenary Christianity, which is the historical, concrete, and categorical communication of grace through Jesus Christ and lived out in the Church.

Having said this, we can see that there is no opposition between the theory of anonymous Christians and missionary concerns. The historical event of Revelation is by no means a mere "supplement" to transcendental experience, without which the latter would be fulfilled. Anonymous Christianity remains a fragmentary, incomplete, and unfinished reality if it does not join the full, explicit Christianity. The latter therefore exists in view of its realization in explicit Christianity, and the Church's missionary task is in this order of things, analyzed as necessary and indispensable to its completion.

It's surprising that such an optimistic concept as Rahner's, which tries to understand dynamically the universal vocation of salvation of all people in Christ, should have had a less than favorable reception even among Catholic theologians.

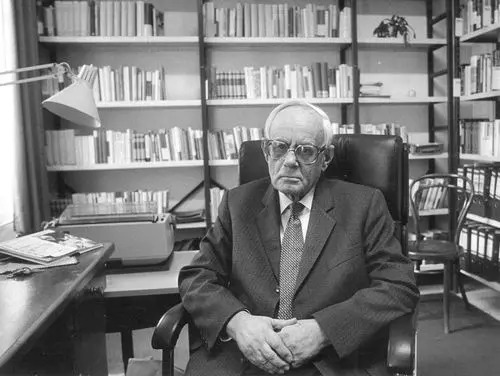

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-1988) is perhaps the most famous critic. For the Swiss theologian, Rahner's theology implies a neglect of the Cross and Redemption. It also leads to a misunderstanding of Christian Revelation, and of what it means to be an authentic believer. Balthasar recognizes the need for dialogue with contemporary humanism, but this can lead to a denaturalization of the Christian being itself. For him, the term "anonymous Christian" implies an undue reduction of Christian specificity, which has now become a worldly humanism according to this view.

Rahner surely wanted to open the door to the many without conscious faith in Christ, a concern already long-standing in theological thought. The Fathers of the Church spoke of the semina Verbi present in the elements of truth of other religions. Saint Thomas Aquinas used the concept desiderium naturale videndi Deum, and theological tradition speaks of "implicit faith" or "baptism of desire". These concepts are not far removed from what Karl Rahner meant by his term "anonymous Christians," a kind of common ground between believers and non-believers that enables dialogue, developing a preparation for the Gospel and even a soteriology for the non-baptized.

It is probably the use of Christians indiscriminately that poses the difficulty because it does not account for Christian specificity, as Balthasar denounced; and because non-believers can feel violated by being called Christians. Anonymous Christian would do neither of them justice.

There can be no doubt about Rahner's sincere attempt to propose Christian truth to today's post-Christian world. His intention was legitimate, but the terminology of "anonymous Christians" was controversial, because it was perhaps somewhat clumsy. Ultimately, the mission of evangelization based on the doctrine of anonymous Christianity highlights the different aspects of the world in which missionary activity takes place: a world of cultural, ideological, and even religious pluralism awaiting its fulfillment in Jesus Christ.

Suggested further reading:

- Balthasar, Hans Urs von, The moment of Christian witness (1st ed.), San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1994.

- Rahner, Karl, Foundations of Christian faith: an introduction to the idea of Christianity, New York: Crossroad, 1978. Especially pages 126-131 and 305-307.

- Rahner Karl, “Anonymus Christians and missionary duty of the Church” in IDOC internazionale (Vol. 20, 1970), 77-93.

- Sesboüe Bernard, "Karl Rahner et les 'chrétiens anonymes,'"Études, November 1984, 521-535.

About the author

Rodrigo Martínez Murillo is a Catholic priest with studies in humanities, philosophy, and theology. His field of interest is Christology and theological anthropology. His vast European experience covering several countries has led him to take an interest in 20th-century theology, especially in French and German thinkers.