The ghosts of the Second World War still haunt Europe. As critical anniversaries have come and gone and the last surviving veterans pass away, the specter of the war’s origins continues to arouse passions across Eastern and Central Europe. The series of international spats that have resulted have been one factor among many in bringing the already fraught EU-Russian relationship to its coldest moment since 1991.

Two years ago, Polish delegates at the European Parliament proposed a motion stating that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union had initiated World War II as partners eighty years earlier when they invaded Poland. In the resolution, the European Parliament equated the two totalitarian regimes’ crimes against humanity, then condemned “the efforts of the current Russian leadership to distort historical facts and whitewash crimes committed by the Soviet totalitarian regime and [considered] them a dangerous component of the information war waged against democratic Europe.” The resolution passed with overwhelming support.

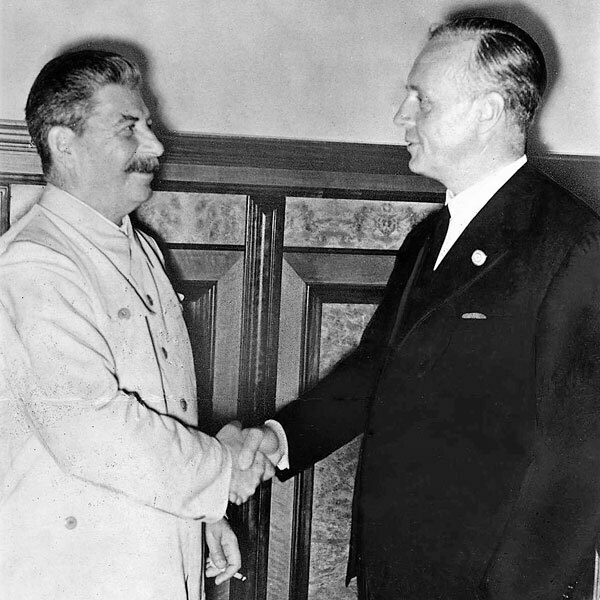

In response, an outraged Vladimir Putin devoted an entire hour-long speech in December 2019 at an informal summit of CIS leaders in Moscow. There, President Putin, playing historian, delivered a detailed lecture on the origins of the Second World War while waving archival documents. He declared that “the Soviet Union was trying to the utmost to use every opportunity for establishing an anti-Hitler coalition, held talks with military representatives of France and Great Britain, thus attempting to prevent the outbreak of World War II, but it practically remained alone and isolated.” He presented a different narrative of the war’s origins, stating that “Poland”—not the USSR—“generally contributed to the beginning of the Second World War” with its “Machiavellian” and “mercenary” foreign policy. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Hitler and Stalin, he concluded, was a defensive measure of last resort for the Soviet Union, and ultimately a wise one.

Why so much vitriol over historical events long past, committed by statesmen long dead representing governments that, in several instances, no longer exist? The reality is that the Second World War retains enormous symbolic importance to governments of Central and Eastern Europe. The bloodiest front in the Second World War—the region between Moscow and Berlin—witnessed over 30 million deaths. One in five Polish citizens and one in six Soviet citizens died as a direct result of the war. On the local level, almost every family experienced loss, reshaped in some way by the war. Putin himself is a clear example of the war’s impact: his brother and five uncles died during the war, and his father was crippled. For Putin and many Russians, suggesting that the USSR was not on the right side seems to throw into question the enormous sacrifices made during the war. On the other hand, for most Poles, ignoring the USSR’s role in starting the war, the hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens arrested, deported, or executed by the Soviet regime during the war, or the imposition of a brutal dictatorship at the war’s end is equally unacceptable.

Long the great legitimizing event of Soviet history—victory in the war proving that all the horrors of Stalinism had been necessary—World War II has again returned as justification for Russian foreign policy the last fifteen years.

There are practical stakes in these battles. The staggering losses, and the geopolitical changes that resulted from the war, have made the war an essential touchstone for defining nationhood across Eastern Europe. This is particularly true in Russia, where the historical record remains entangled with contemporary foreign policy. Long the great legitimizing event of Soviet history—victory in the war proving that all the horrors of Stalinism had been necessary—World War II has again returned as justification for Russian foreign policy the last fifteen years.

In addition, the historical analogy of the war has been used repeatedly in the ongoing competition between Putin and the West. Drawing from the World War Two metaphor, Putin has painted a portrait of a Russia encircled by hostile adversaries as in 1939, even comparing the spread of liberal values to the danger of Nazism. The use of the label “fascist” in Russian media in regards to adversaries in Ukraine, Georgia, the Baltic States, and even NATO has been one of many signs of this rhetorical shift. That metaphor has thus provided historical justification for aggressive moves in Russia’s near abroad. First, there remains a sense that Russia’s neighbors owe Russia for the huge sacrifices made by the Red Army in liberating their territories from the Nazis. This, in turn, has justified Russian intervention in their domestic affairs. For instance, the relocation of monuments to the Red Army in Tallinn, Estonia, seen as a snub of the Russian role in “liberating” Estonia, triggered the 2007 cyberattacks, which shut down parts of the Estonian government and economy.

There are thus serious consequences for reinterpretation of the outbreak and conduct of the war – the sorts of battles that led to the public spat between Poland and Russia in 2019. Several states in Eastern Europe have criminalized public criticism of deeply-held historical narratives. Poland, for instance, has enacted laws against the denial of Nazi or Soviet crimes, but also, more controversially, individuals accusing Poland of “participating, organizing or being responsible for communist or Nazi crimes.” Nowhere has this trend been truer than in Russia, where members of the ruling United Russia party have repeatedly passed educational reform bills since 2013 rewriting the country’s history textbooks. They now provide little detail about Stalinist repression or the country’s role in the origins of World War II, other than that Soviet forces liberated “western Ukraine and western Belarus” in 1939. Not mentioned is that those Soviet forces were in fact invading independent Poland and doing so in conjunction with Nazi Germany. In May 2014, Putin signed the “Law against the Rehabilitation of Nazism.” This bill criminalized criticism of the Red Army or the Soviet state during the war. Vladimir Luzgin, a car mechanic from Perm, was the first to be sentenced under the new law, accused of posting an article on a social media site that said that Nazi Germany and the USSR “attacked Poland together, unleashing World War II.” He was fined 200,000 rubles; he eventually fled the country.

It seems unlikely that these conflicts over history will come to an end any time soon. The stories being told are too important to national identities across the region. Nevertheless, the battles being waged are worth studying, as changing narratives about the Second World War offer some guide to the strategic views and public sentiments of the area’s regional powers. Perhaps someday, more honest histories will prevail, and with them, greater stability and peace in the region.

Further recommended reading on the subject

- Sergey Radchenko, “Vladimir Putin Wants to Rewrite the History of World War II,” January 21, 2020, Foreign Policy, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/01/21/vladimir-putin-wants-to-rewrite-the-history-of-world-war-ii/.

- Roger Moorhouse, The Devils’ Alliance: Hitler’s Pact with Stalin, 1939-1941 (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

- Mark Edele, “Fighting Russia’s History Wars: Vladimir Putin and the Codification of World War II,” History and Memory, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2017), pp. 90-124.

About the author

Ian Ona Johnson is the P.J. Moran Family Assistant Professor of Military History at the University of Notre Dame and a faculty fellow of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. He is the author of Faustian Bargain: The Soviet-German Partnership and the Origins of the Second World War (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Originally published by at nanovic.nd.edu on July 28, 2021.

This article is part of a new Nanovic Institute initiative, the “Europe in the World” (EITW) project, which features public-friendly analyses and commentary of Europe’s political, social, and economic relations with the rest of the globe.