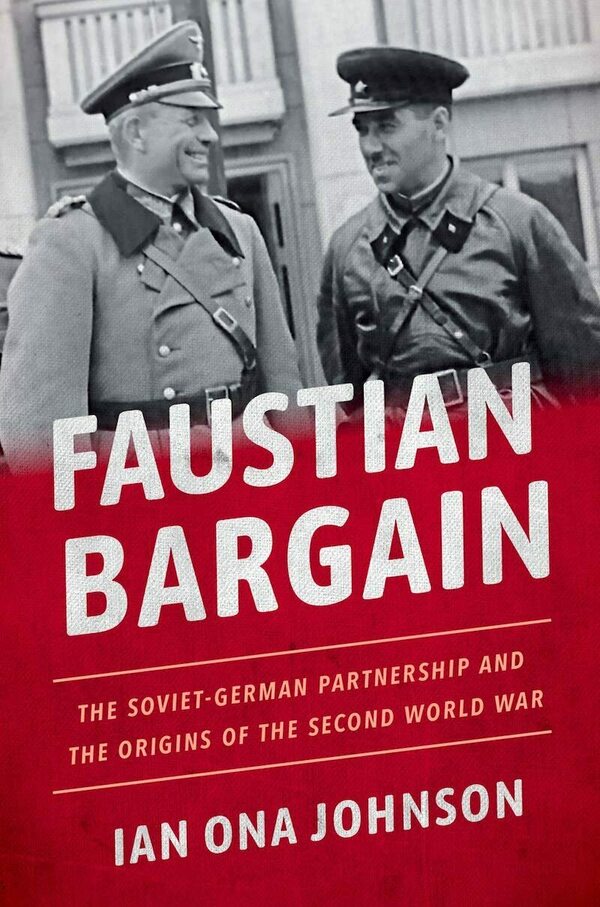

“5 Questions with … ” is a series featuring short interviews with leading scholars and practitioners whose work directly speaks to the key themes of Europe in the World (EITW). For the second installment, Ian Ona Johnson, the P.J. Moran Family Assistant Professor of Military History at the University of Notre Dame and a faculty fellow of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, talked to us about his recent book, Faustian Bargain: The Soviet-German Partnership and the Origins of the Second World War (Oxford University Press, 2021). For Faustian Bargain, Johnson recently received the Society for Military History’s 2022 Distinguished Book Award for best first book, given to a publication from the past three years.

The EITW Editors: Simply put, what is your book about? And what is the central point you make?

Ian Ona Johnson: Faustian Bargain: The Soviet-German Partnership and the Origins of the Second World War recounts twenty years of on-again, off-again cooperation between the German military (the Reichswehr) and the Soviet Union. Their partnership began at the end of the First World War, with Germany defeated and the Soviets in the midst of a civil war. Their shared hostility to the new international order brought them together publicly in 1922 with the Treaty of Rapallo. Simultaneously, the Soviets and Germans began a secret military partnership aimed at rebuilding Soviet and German military power. At first, cooperation centered on the transfer of banned industrial production—particularly aircraft and chemical weapons—from Germany to the USSR. Beginning in 1924, the partnership expanded. Four joint military bases opened in the 1920s, specializing in armored warfare, aviation, and chemical weapons. Prototype aircraft and armored vehicles soon followed, providing the basis for later German rearmament. In exchange for allowing Germany to train officers and test technology, the Soviets received assistance in training thousands of their own officers, capital to greatly expand Soviet military industry, and access to German technology. The pact was suspended in 1933 but resumed in 1939 with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. I argue in Faustian Bargain that this secret partnership provided the basis for rapid German rearmament under Hitler, and eventually led to the outbreak of the Second World War.

Editors: What is one of the most surprising findings you encountered in your research for this book?

Johnson: How much was known at the time about secret Soviet-German cooperation, and how little was done to stop it. In 1926, a British journalist broke the news of illicit German rearmament work then ongoing in the USSR. It created a domestic furor in Germany, leading to a vote of no confidence in the German government. Yet the British and French, supposed superintendents of the international order, did nothing, and cooperation continued to expand. Two years later, a scandal broke involving a German naval officer, his mistress, and a bizarre range of German naval activity—including the purchase of a film studio to create pro-navy propaganda, attempts to draw gold out of seawater, and plots to refloat shipwrecks with icebergs. It also became apparent that Germany was building combat equipment (including submarines and aircraft) in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. But once again, the Allies did nothing. That consistent refrain of inaction only changed after it was much too late. Only by 1936 did British and French policymakers realize that Germany had rearmed beyond their capacity to stop them, short of a major war. Fifteen years of failure to enforce existing treaties proved devastating to efforts to maintain peace in Europe.

Editors: What novel perspective does your book or research provide on Europe’s political, social, or economic relations with the rest of the globe today?

Johnson: I have argued that the Western democracies generally failed the difficult test of the interwar period. Their leaders and their publics lost confidence in the value of the order they themselves had established at Paris in 1919, which was predicated on self-determination, free trade, and international law. Simultaneously, there was a growing assumption that war was a thing of the past, at least within the boundaries of Europe. That combination of irresolution and naivete created an opportunity for revisionist powers—most notably Germany—to rearm in violation of international law and launch a new, even more terrible war. France and Great Britain responded to Germany’s twenty-year program of rearmament with real rearmament of their own only when it was too late to stop Germany short of war around 1937. We have seen the consequences of a mostly-disarmed Europe in the context of the war in Ukraine; none of the states of Europe possessed the capacity to deter Russian aggression or act militarily, absent American assistance. The result has been the outbreak of the worst conflict in Europe since the Yugoslav Wars ended two decades ago.

Editors: What are some additional works—by you or others—one can consult for further reading on these issues, or what recent works about Europe do you find particularly insightful or inspiring?

Johnson: The best books on Soviet-German military cooperation as a whole are Manfred Zeidler’s Reichswehr und Rote Armee [Reichswehr and Red Army] (R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1993) and Sergei Gorlov’s Sovershenno Sekretno [Top Secret] (Institut vseobshchei istorii Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk, 1999). Roger Moorhouse’s The Devils’ Alliance (Basic Books, 2014) is an excellent and highly readable account of the final consequences of the Soviet-German partnership between 1939 and 1941. Right now, I’m reading Alexander Mikaberidze’s The Napoleonic Wars (Oxford University Press, 2020). It is the best book I’ve read to provide a truly global perspective on Europe’s era of revolution and war between 1792 and 1815. It shows how the conflict, its ideology, and its consequences not only impacted Europe, but reshaped the broader world, too. I recommend it.

Editors: Is there anything else you want people to know or want to tell our readership?

Johnson: History matters. President Vladimir Putin, who has constantly sought to use history to legitimize his foreign policy, referenced the Second World War fourteen times in his speech effectively declaring war on Ukraine. The stories we tell ourselves about the past shape us and our decisions. As such, I hope readers will seek out and support those historians who do the difficult archival research and strive as best they can for objectivity and careful analysis in their writing.

Further recommended reading on the subject

- Roger Moorhouse, The Devil’s Alliance: Hitler’s Pact with Stalin, 1939-1941 (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

- Joe Maiolo, Cry Havoc: The Arms Race and the Second World War, 1931-1941 (London: John Murray, 2010)

- Ian Ona Johnson, “The Long Shadow of 1939: The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the Politics of Memory in Eastern Europe,” Europe in the World, August 19, 2021. Accessible here.

About the author

Ian Ona Johnson is the P.J. Moran Family Assistant Professor of Military History at the University of Notre Dame and a faculty fellow of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. He is the author of Faustian Bargain: The Soviet-German Partnership and the Origins of the Second World War (Oxford University Press, 2021).